1521 Vote

Ostad Elahi’s life and works

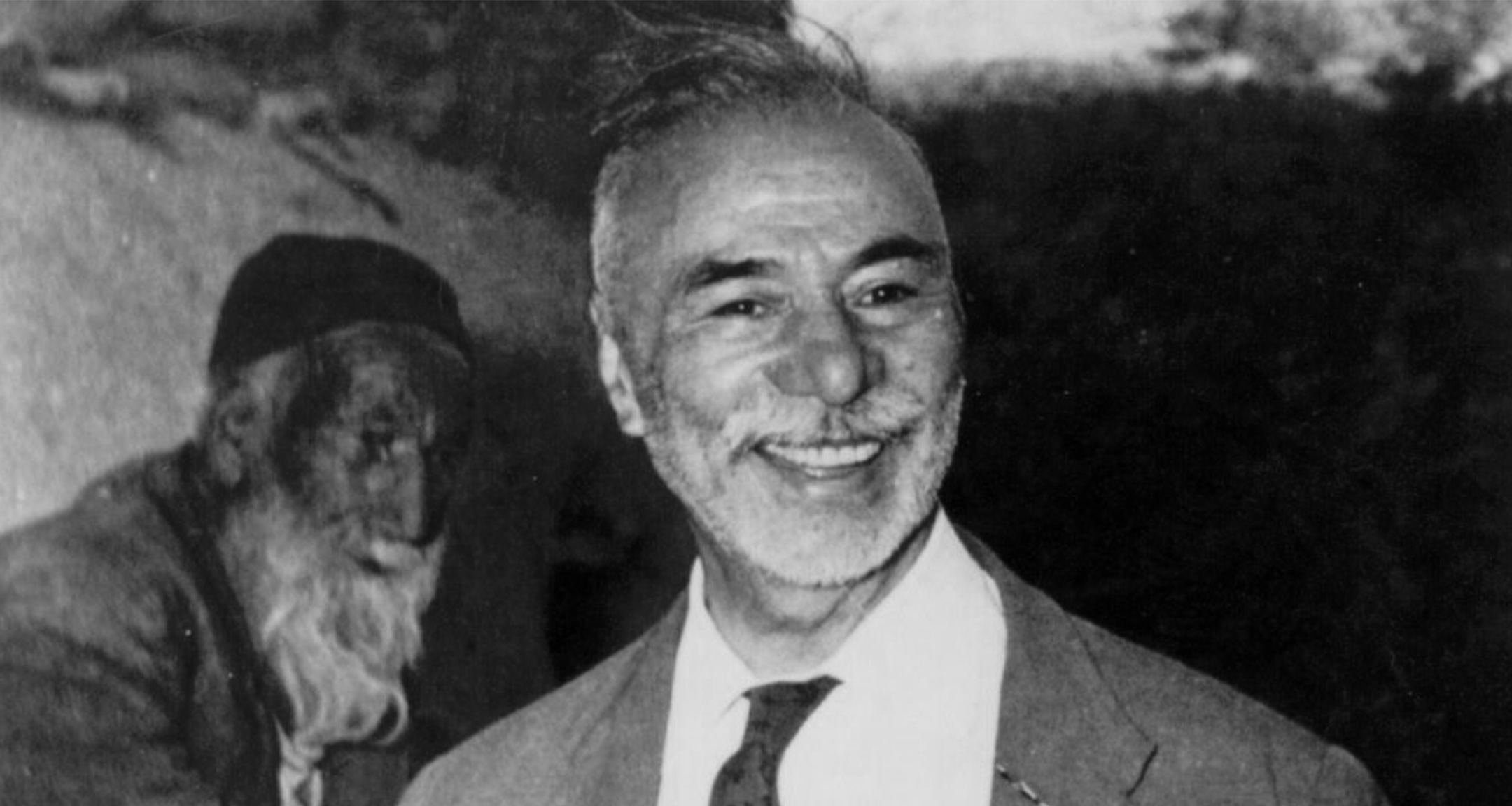

Ostad Elahi was born on September 11, 1895. On the occasion of his 116th birthday, it was only natural to pay him homage by reviewing some of the salient aspects of his life and works. In the preface to his translation of Knowing the Spirit (SUNY, 2007), Prof. James Morris draws from various sources, including autobiographical conversations and remarks by Ostad himself. This lively portrait of an outstanding 20th century spiritual figure manages to uncover the inner connections between the rich and varied experiences of a lifetime and the central notions of a philosophy. The following excerpt is published with the kind authorization of the author and SUNY Press.

Nūr ‘Alī Elāhī—or Ostad Elahi (“Master” Elahi), the honorific by which he is most widely known today—was born on September 11, 1895 in Jeyhunabad, a village in western Iran(1). The outward course of his life, as he described it in autobiographical conversations and remarks during his later years,(2) falls into three distinct periods: his childhood and youth, entirely devoted to traditional forms of ascetic and religious training; his active public career, for almost thirty years, as a prosecutor, magistrate, and high-ranking judge; and the period of his retirement, more openly devoted to spiritual teaching and writing (including the composition of Knowing the Spirit), when he became well known as a religious thinker, philosopher, and theologian, as well as a musician. Ostad Elahi’s own later description of those outward events, summarized in a few of his sayings quoted further on, helps bring out the inner connections between those different periods of his life and the broader lessons he was able to draw from those very different activities and experiences.

Childhood and Youth

Ostad Elahi’s father, Hajj Ni’mat Jayhunabadi (1873-1920), was a prolific writer and mystical poet, from a locally prominent family.(3) Among his many writings was his major work The Book of Kings of the Truth,(4) an immense poetic compendium of traditional spiritual teachings. From early childhood on, Ostad Elahi led an ascetic, secluded life of rigorous spiritual discipline under his father’s watchful supervision. He also received the general classical education of that time, with its special focus on religious and ethical instruction as the foundation of his training. It was during those formative years of his youth, completely devoted to contemplation and study, that he developed the basic foundations of his later philosophic and spiritual thinking. In his own words:

I began fasting and spiritual exercises at the age of nine, and kept them up continuously for almost twelve years, taking only a few days between the forty-day periods of spiritual retreat. Usually my evening meal to break the fast was only bread and vinegar. I almost never went out of the retreat house, and I only associated with the seven or eight dervishes who were allowed to enter it. When I finally left the retreat house at the end of those twelve years and came into contact with other people, I couldn’t imagine that it was even possible for human beings to tell lies.(5)

The following story poignantly conveys both the special role of his father’s guidance in that initial stage of his spiritual discipline and the lasting lessons that he was able to draw from that intense period of spiritual training:

Ordinarily during my childhood I was always involved in spiritual exercises. Only occasionally did we have a few days’ break between two forty-day periods of spiritual retreat and fasting. During one of those periods of spiritual retreat, someone brought me two strings of delicious dried figs. I set them aside specially for myself, and each night I broke my fast in a state of intense desire for those figs; after breaking the fast I would take great pleasure in eating a few of them, until the forty days were over. On the last night of the retreat I had a dream in which I saw each person’s spiritual exercises being recorded. I saw my own as a wall that I had built with beautiful bricks, except that a corner of each brick was broken off and incomplete. … The next day my mother, as she usually did, asked my father’s permission to prepare an offering meal. “No,” my father replied, “because this person’s spiritual exercise is imperfect, he’ll have to perform another forty days of fasting and retreat, as a fine, so that his mind won’t be filled with figs.” The point of this is that the essential condition for spiritual exercise and fasting is not just doing without food. Rather, the person traveling the spiritual path must always have their attention on the Source and must cut their attachments to everything else. Otherwise, there are plenty of people who go without eating something. (AH, 1877)

Ostad Elahi’s lifelong devotion to spiritual music, and in particular his mastery of the tanbūr (a lutelike stringed instrument especially used for gatherings of religious music and prayer), also date from his early childhood: “There are two things to which I’ve always unsparingly given my time: one is the tanbūr and the other is traveling the spiritual Path.”(6) The following story illustrates not only the role of music already in Ostad Elahi’s childhood, but also the special inner affinity with nature and other creatures which was a distinctive trait of his character throughout his life:

When I was a child, they brought me a partridge one day. That partridge loved the sound of the tanbūr. As soon as I picked up my instrument, the bird would sit right next to me. And once I started playing she would become intoxicated by the music and begin to sing, gripping my hand and pecking at it with her beak; that state of drunkenness made her completely wild. At night, the partridge slept on a shelf in my room. Early one morning, when I wanted to go back to sleep, she began to sing. I grumbled at her to be quiet; and immediately she lowered her head sadly and stopped singing. From that day on, whenever the partridge woke up in the early morning, she would stand at the foot of my bed and pull softly on the covers, cooing softly. If I didn’t react, after two or three tries she understood that I was still sleeping and went away. But if I said to her “Mmmh, what a pretty voice!” she would begin to sing. (AH, vol. 2, 162)

While the outward course of Ostad Elahi’s life was eventually to take him away from this purely contemplative, traditional way of life, he always continued to acknowledge the foundational role of this early period of spiritual discipline and retreat and his father’s guidance during that time:

My mother was anxious about my worldly education, and she always used to ask my father: “So when is he going to do his studies?” My father replied: “As long as his domineering self (nafs) hasn’t awakened, let him complete his spiritual training, so that it won’t be able to have an effect on him. After that he’ll study.” Things turned out exactly as my father had predicted. I began my spiritual training when I was nine, and that course of spiritual discipline lasted for twelve years. After that I began to study, and desires and passions no longer had any effect on me. (AH, 1964)

Professional Life and Judicial Career

Some ten years after his father’s death in 1920, Ostad Elahi left his spiritual retreat and eventually settled in Tehran, where he worked in the Registry Office and began to study civil law. This radical change of life was a sharp break with the local tradition, which would have destined him to an entirely contemplative way of life. This change of life, as he later explained, was necessary for him in order to deepen his thinking and to test his ethical and religious principles in the face of all the difficult demands of social and professional life.

God made me enter the public administration and government work despite my own aversion for that. He made me become a judge by force and gave me difficult judicial assignments. But afterwards I discovered that in each of those posts were concealed thousands of points of wisdom, such that even a multitude of philosophers and sages gathered together couldn’t have designed such plans. (AH, 1966)

In 1933, Ostad Elahi successfully completed his studies at the national school for judicial officials. His professional abilities and sense of equity and good judgment were quickly recognized, so that he was invariably entrusted with responsibility for the most difficult assignments. A number of dramatic incidents came to demonstrate the truth of his later observation, “When I was a judge I was always prepared to be permanently dismissed rather than hand down a single judgment contrary to what was right and just” (AH, 2037). For almost thirty years he was appointed to positions of increasing responsibility throughout the country, sometimes as public prosecutor or examining magistrate, and eventually as an associate justice and then president of the Court of Appeals.

Throughout this period of his career as a magistrate, Ostad Elahi continued to devote a great deal of time to his personal studies and research, especially in the areas of philosophy and theology. Although we know little about the unfolding course of his thought during those years, it is clear that this period was extremely productive and filled with all sorts of experiences that richly nourished his studies and helped him to elaborate his later works. One of the stories he later recounted from that period vividly illustrates the broader spiritual lessons he drew from the experiences of that time:

During the time I was an investigative magistrate in Shiraz, I hadn’t brought my family along with me. I rented part of a house; the owner occupied one side of the house, and I lived on the other side. One night a special spiritual state came over me, and I wanted to pass the night in solitude and seclusion, concentrating on prayer and meditation and my own spiritual state. The owner of the house had invited lots of people, and it was getting noisy. … I shut my door and opened my window facing the street, but there were two porters just outside beneath the window, who were busy discussing their problems. So I closed the window and went up on the roof, but there were already two women up there talking. I had to climb down, and I went off to visit a local saint’s shrine. The guardian of that shrine was an upright and respected dervish. “I’m going into your room and I want to concentrate on my spiritual state,” I told him. “Please don’t let anyone come in and disturb my retreat.” He agreed, so I went on into his room, still wanting to devote myself to that spiritual state. Just at that moment two women came up and began to joke around with that guardian, who was more than a hundred years old. I was at the end of my rope. I came out of the room and asked them to leave the dervish alone, but it turned out they wanted to chat with me too! In short, that special state of mine disappeared; and no matter what I did I wasn’t able to concentrate. “O Lord,” I said, “so you’re still testing me? Well by God, it’s up to You. Thy will be done!”

Later on, in the spiritual world, they told me that the aim of all this was to prevent me from secluding myself, because I’d recently been a little too withdrawn, and that I ought to participate in social occasions in accordance with my profession. It’s not right to try to withdraw from society. Instead you must go out into society while still staying true to your self. … To be in society and still remain moral, that’s what counts. (AH, 1924)

Throughout this period, spiritual music continued to have a very important place in Ostad Elahi’s life. He was soon acknowledged by musical specialists to be a great virtuoso of the tanbūr, and he enriched its repertoire by composing many original musical pieces of his own. This musical practice and creation was always integrally connected with his wider spiritual life, as one can see in such remarks as the following: “I’m always thinking of my master. In music, whenever I play a piece or a melody I’ve learned from someone, I say a prayer for that person if they’re still alive; and if they’re dead, I ask God’s mercy for them” (AH, 1950).

In his lessons and oral teachings given later in life, Ostad Elahi often illustrated his points with anecdotes drawn from this period, in a way that suggests how he was able to discover profound spiritual lessons in the “ordinary” encounters and incidents each day brings. As he once put it, “It is in everyday life that I’ve learned the most lessons about the underlying order of the universe. This world becomes a place for spiritual edification once we discover how to draw those lessons from it-even from the flight of a mosquito.” The following memorable story is a typical example:

One day, during the time I was head of the court in Jahrom, I was outside of town when I saw a very beautiful orchard and fields out in the middle of the desert. I asked whose it was, and they told me: “It belongs to a person who started out with absolutely nothing and has now come to this point. One day he was passing by there when he noticed some moisture under the rocks on the surface. He dug down a little deeper with his walking stick and saw that the wetness increased. With a great deal of toil and trouble he constructed an irrigation tunnel, and now he’s been busy with that for some twenty years.” Later I met that man, and I was very friendly and encouraging with him. As he described himself: “When I first came here I was alone and without any money. I had just enough to buy a bucket and a shovel, but with a lot of hard work I was able to channel the water, and now I’ve reached this point.” All those orchards and fields he had were the result of this principle of persistence and perseverance. (AH, 1936)

Another similar personal story, from somewhat later in his life, also illustrates the sense of humor that was always one of his distinctive traits of character:

Last night I woke up at midnight as usual for my nightly prayers and devotions. But because I was feeling slightly ill I acted a bit lazy and said to myself: “I’ll pray tomorrow morning,” and I went back to sleep. Of course the next morning I performed my prayers, and then I began to do my exercises. Now I had never dropped one of the exercise weights before, but one of those weights slipped out of my hand and fell right on my toes. It hurt for an hour. God had reprimanded me to exactly the same extent as I’d been lazy with Him-there was something almost comical about it! I was extremely happy about that incident, and I bowed down to God in gratitude on the spot. “Now I know that You love me,” I told him, “and that You’re always watching over me. Otherwise I might have been lazy other nights as well.” (AH, 2002)

One final incident dating from this period strikingly underlines yet another key aspect of Ostad Elahi’s character that is evident in all of his teaching, which was his own rigorous insistence on actually living, practicing and clearly demonstrating through one’s own life and actions the abstract principles of spiritual and religious truth. A student of his noted that one day while Ostad Elahi was explaining that we should not reject other religions and faiths, he added by way of illustration:

One time in Kermanshah, while I was out walking with a group of friends, we passed by a place where some Jews were praying. To the bewilderment of my companions, I went in and began to pray along with them. At first those in the synagogue thought I was trying to make fun of them; but when they understood that that wasn’t the case, they were very pleased. We should never miss an occasion to pray under the pretext that it would involve praying with Jews, Christians, Muslims, or any others. (AH, vol. 2, 43)

The Final Period: Writing and Teaching

Ostad Elahi retired from the judiciary in 1957, and only after that did he really begin to discuss more publicly his own way of thinking. During this period he published two major scholarly works, Knowing the Spirit (Ma’rifat ar-Rūh) and Burhān al-Haqq (Demonstration of the Truth), which were authoritative statements in their respective fields, as well as an extensive commentary on his father’s immense spiritual epic.(7) At the same time, he began to develop much more fully the practical spiritual dimension of his teaching through the oral teachings and instruction that he shared with a few friends and students who gathered with him at his home until the end of his life, in 1974. Two lengthy volumes of Ostad Elahi’s sayings and spiritual teachings—including all the anecdotes cited previously—have so far been published on the basis of notes written down by his students during that period.(8)

Those collected sayings bear the marks of profound spiritual inspiration, while they also reveal a penetrating understanding of human nature, a constant concern for intelligibility, and the sensitive use of immense learning in the service of a creative and original way of thinking. The following concluding remarks, from the last years of Ostad Elahi’s life, beautifully highlight the source and intentions of his later spiritual teaching and the way all his instruction continued to be drawn from his own experience and practice:

I have not passed over any subject in silence: all that is needed is a grasp of the question and the aspiration (to understand). And that aspiration comes from the angelic spirit. In these things I say to you my purpose is not to recount stories, but to give you sound advice. I am not able to tell someone something until after I’ve put it into practice and tried it out for myself. As for the points that I do mention, I won’t express anything until I have completely investigated it to such a degree that no one could object to it, whether in this world or the next. I have spoken with each person to the extent that they could understand. But I’ve still not told anyone all there is in my heart. (AH, 2074)

These are the things that I’ll always love, that will please me and make my spirit rejoice even if I’m no longer in this world: to see those close to me wholeheartedly united and working together, not squabbling and thinking of themselves; to see them striving to do what is good and to serve others, always eager to act humanely, for the sake of others, and truly to care for them. (AH, 2026)

Ostad Elahi’s Published Works: The Place of Knowing the Spirit

Ostad Elahi continued to write on many subjects throughout his life, as evidenced by the many unpublished notebooks and manuscripts included in the exposition at the Sorbonne organized in celebration of the centennial of his birth in 1995.(9) However, it was only after his retirement from the judiciary that he began to publish his works, beginning with the elaborate theological discussions of Burhān al-Haqq (Demonstration of the Truth) in 1963, which was greatly expanded in later editions; his commentary on his father’s vast spiritual poem, the Shāhnāmeh-ye Haqīqat, in 1966 (Haqq al-Haqā’iq); and finally the relatively much shorter volume of Ma’rifat ar-Rūh (Knowing the Spirit), in 1969.

Burhān al-Haqq is a highly complex theological and spiritual work, dedicated to showing the inner concordance and common spiritual aims shared by the Qur’an, the teachings of the Shiite Imams, and original teachings and practices of the spiritual order of the “people of the Truth” (Ahl-i Haqq), the dominant popular spiritual tradition in Ostad Elahi’s native region of western Iran, whose teachings and legends (originally transmitted in a rare regional Kurdish dialect) had earlier been recorded in Persian verse in his father’s immense Book of Kings of the Truth.(10) Ostad Elahi’s procedure in Burhān al-Haqq resembles that of Knowing the Spirit insofar as he constantly juxtaposes the relevant scriptural verses of the Qur’an with the traditional Shiite teachings (and those of the great saints of the Ahl-i Haqq) in order to evoke in his readers an awareness of the vast range of deeper shared spiritual truths underlying each of those traditions. The same metaphysical issues central to Knowing the Spirit are often discussed there, but usually in more traditional symbolic and religious language; the explicitly universal philosophical terminology and arguments adopted here are not so much in evidence in that earlier volume.

However, the essential bridge between Burhān al-Haqq and Knowing the Spirit-and in a way, to the more accessible and wide-ranging oral spiritual discussions of that same period later revealed in detail in Athār al-Haqq-was Ostad Elahi’s constant concern with responding to the spiritual questions and requests for guidance that he increasingly received from people in all walks of life, not only Iranians, but now expanding to include famous scholars, musicians, students, and seekers who came to visit him from throughout Europe and America.(11) Thus the very genesis of Knowing the Spirit, as he points out in his introduction to this work, had to do with key questions first put to him about our knowledge and awareness of the “Spirit” by readers of Burhān al-Haqq. As a result of such questions, within a few years he began to add to his subsequent editions of Burhān al-Haqq (roughly two hundred pages in the original version) much longer appendixes of more than four hundred additional pages, recording his responses to the very diverse spiritual questions of this multitude of inquiring visitors; many of those questions and responses extend far beyond the more limited, original theological contexts of that book.(12) As such, this first revealing summary of his actual personal efforts of teaching and guidance, in its later editions, was already almost as long as the more extensive verbatim collections of his oral teachings recorded in the later volumes of Athār al-Haqq.

(1) ^ Almost all writings and publications in recent decades now use the shorter honorific, Ostad Elahi. The most detailed biographical study to date, focusing primarily on Ostad Elahi’s accomplishments as a musician, is certainly Jean During’s recent L’Âme des sons: L’art unique d’Ostad Elahi (1895-1974), (Gordes: Editions Le Relié, 2001). In addition one of my PhD students is now preparing a biographical study focusing on Ostad Elahi’s juridical career and related ethical and social teachings.

A great deal of additional biographical information, including a wealth of photographs from all periods of Ostad Elahi’s life and accounts by people who had known him personally, was brought together in the volume entitled Unicity (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1995), prepared for the international UNESCO-sponsored commemoration of the centenary of his birth in 1995. Especially important, from a biographical perspective, was the extensive collection of materials relating to his life (including his library, musical instruments, CDs of his music, videos, etc.) assembled for the commemorative exposition held at the Sorbonne in that year. Much of that exposition material is still accessible at the bilingual website established on that occasion (www.ostadelahi.com).

Additional helpful biographical references—including ongoing lecture, concert, and seminar series on Ostad Elahi and his teachings—can be found on the following closely related websites (all with English-language versions): www.fondationostadelahi.org; www.nourfoundation.com; and www.malakjan.com. The latter site is devoted to his younger sister, Malek Jān (better know by her nickname “Jānī”), 1906-1993, who became an influential and highly revered spiritual figure in her own right.

(2) ^ Those sayings and spiritual teachings were recorded by his students and eventually published in the two massive volumes entitled Athār al-Haqq (Traces of the Truth), ed. Bahram Elahi, volume I (Tāhūrī, 1978) and volume II (Jayhūn, 1992). The sayings quoted later are all drawn from these two volumes; the quotations cited here are mainly from autobiographical chapter 24 of volume I, identified by their number in that volume.

Two short collections of Ostad Elahi’s translated sayings excerpted from Athār al-Haqq in highly abridged form were published, in both English and French, on the occasion of the 1995 centenary celebrations: 100 Maxims of Guidance, by Ostad Elahi, and Words of Faith: Prayers of Ostad Elahi (both Paris: Robert Laffont, 1995).

(3) ^ Ostad Elahi’s discussions of the extraordinary spiritual personality of his father are concentrated in chapter 23 of Athār al-Haqq (vol.1), as well as in many of the stories recounted in chapter 24. Although his family grew up in a remote Kurdish area of western Iran, ”Hajjī Ni’mat”, as he was familiarly known, was one of the main spiritual teachers memorably described early in Gurdjieff’s famous Meetings with Remarkable Men. (Another of my PhD students in Paris is now preparing a pioneering study of Hajjī Ni’mat, including an edition of part of his own autobiographical account of his remarkable, original spiritual illumination.)

(4) ^ Shāhnāmeh-ye Haqīqat, a Persian (and Kurdish) mystical epic poem of more than 15,000 lines, edited by H. Corbin, in the collection Bibliothèque Iranienne (Tehran and Paris: Institut Français, 1966), as well as in the subsequent corrected edition and commentary by Ostad Elahi (Haqq al-Haqā’iq) discussed at the end of this biographical section (see note [10]).

(5) ^ Athār al-Haqq, vol. 1, saying no. 1873. Subsequent sayings quoted from that work are identified simply by their reference number (in parentheses after the saying).

(6) ^ For a detailed study of Ostad Elahi’s remarkable music and its spiritual effects and significance, see the recent book by Jean During (L’Âme des sons…) in note [1]. Professor During and Dr. Shahrokh Elahi (Ostad Elahi’s youngest son, in whom he confided much of his musical knowledge) have cooperated in the recent preparation and publication of a series of widely accessible CD versions of recordings of Ostad Elahi’s music made late in his life.

(7) ^ Burhān al-Haqq (Demonstration of the Truth) (1st edition, Tehran: 1963; 7th edition, 1985); Ma’rifat al-Rūh (Knowing the spirit) (1st edition, Tehran: 1969; 4th edition, 1992); and Haqq al-Haqā’iq, his commentary and corrected edition of his father’s long poem, Shāhnāmeh-ye Haqīqat (Tehran: 1969).

(8) ^ See the full references to Athār al-Haqq at note [2]; the 1,200 pages of these two volumes alone would correspond to at least ten volumes in an adequately annotated, complete English translation. I have been using draft translations from these volumes in teaching for the past fifteen years and hope to publish a larger collection of selected translations in the near future.

(9) ^ Some of these as yet unpublished manuscripts include various prayers and mediations; an early metaphysical work (1914) dealing with many of the same subjects as Knowing the Spirit entitled Kashf al-Haqā’iq (Unveiling of the Realities); another study of the realities relating to each of the spiritual stages of religion, written in 1933, entitled Haqīqat al-Asrār (The Reality of the Mysteries/Secrets); and a detailed critical study of the foundational spiritual text (in Kurdish) of the Ahl-i Haqq Order, the Kalām-e Saranjām, based on Ostad Elahi’s unparalleled manuscript collection. The centennial commemoration website (www.ostadelahi.com/English/Works) also mentions a collection of poems and a volume of interpretation of the Qur’an in Kurdish.

(10) ^ See the following revealing account from Athār al-Haqq, saying 1827 (chapter 23): ”My father dictated the entire Book of the Kings of Truth [in 15,042 rhymed Persian couplets!] within a period of forty days. I still remember how he walked around the room, immediately and unhesitatingly reciting its verses while I very quickly wrote them down.” Ostad Elahi’s own corrected edition and commentary of that text (note [7]) was based on his own, original hand-written copy of that poetic work.

(11) ^ Those extended question-and-answer sessions recorded in Burhān al-Haqq take up pages 245-655 of the full final edition of that work; the questioners are not identified by name, but often their nationality, profession, and the like are given to help contextualize their questions. The publications and videos prepared for the 1995 centennial commemorations include extensive firsthand accounts and impressions by Ostad Elahi’s notable visitors during this later period of his life, such as the musician Yehudi Menuhin, the choreographer Maurice Béjart, and so on.

(12) ^ Burhān al-Haqq continues to be studied today by ever-growing circles of readers, even outside Iran, who are primarily drawn by the universality of its underlying spiritual teachings, rather than the particular theological issues of its original context. That growing interest among wider, new audiences is an interesting commentary on Ostad Elahi’s allusive remarks about the lasting importance of that work—as well as Knowing the Spirit—in Athār al-Haqq, sayings 1894, 1997, and especially in the following saying:

There are a great many secrets in (my book) Ma’rifat al-Rūh [Knowing the Spirit] that I haven’t even mentioned to you my children, who are nearer to me than anyone. Only after I’m gone will people understand the real lasting value of Ma’refat ar-Rūh, Burhān al-Haqq, and the other books I’ve written. The more people’s level of knowledge increases the more they’ll discover in those writings… Their importance will increase with each passing century… I investigated each subject until I had completely mastered it and there was nothing left that I didn’t know about it: that is my way of inquiry. [AH, 2076]

© This work is protected by copyright. Copyright reserved. All rights reserved.

Go to top

News

News Podcast

Podcast

Recent Comments