111 Vote

High-definition spirituality (1)

Ethics is at the heart of spirituality. We need to be much learned in ethical matters.

Ostad Elahi, Words of Truth, Saying 379, draft of the forthcoming English translation

There is no Nobel Prize (to date) rewarding ethics research, but surely no one would dispute that in this field Ostad Elahi was perfectly learned.

What is meant here by the word “learned”?

Being learned is not merely knowing. A learned individual is first and foremost one who comprehends, not in theory only or through sustained reading, but as a result of self-acquired concrete knowledge. To comprehend a reality is to have concretely experienced it, to have gained first-hand knowledge of some truth.

Indeed, when Ostad Elahi addresses any topic, you have a distinct sensation that he is speaking from personal experience. This lends a particular quality to his words even when they are most direct and simple in appearance: the rigor and precision that you can perceive in them become completely manifest when you focus on the subject by adopting a close-up perspective, zooming in on the details. The same principle governs his music. It has been said that his melodies and improvisations on the tanbur were designed for up-close listening. When he discusses ethical and spiritual matters, even those that seem most familiar, you can sense that the picture he paints is in high resolution to a staggering level.

Specific to human beings

To validate this idea of “high-definition spirituality” you need only examine a perennial question that has been asked and discussed thousands of times: “what is man?”, as the phrase goes. Or more precisely: “What is it that makes us human?”.

From Ostad Elahi’s writings on that question we can draw at least one thing: human nature results from the combination of a terrestrial soul and a celestial soul. Once combined with their terrestrial counterparts, the celestial elements give rise to distinctive traits such as a faculty of reason that has the potential to transform into sound reason. This is the basic tenet of the process of spiritual perfection. On the surface it all seems quite simple, and you might think that it is just restating a well-known idea: man is part angel, part beast. Or as philosophers would put it: “man is a rational animal.”

However, if we were content with such a description, our understanding of things would remain quite abstract. Merely considering that the soul’s fabric is made up of celestial and terrestrial components that somehow combine in an individual gives no precise idea of what concretely takes place when the two are merged. What specific potentials are activated by such a combination? How can we discern and recognize them within us?

Imagine you have been given the recipe for mayonnaise. Let’s say you have, for simplicity’s sake, three ingredients: egg yolks, oil, and vinegar. (You actually need to add a pinch of salt and mustard, but we will leave them out for this demonstration). If you have never made mayonnaise, there is strictly no way you can guess the final result from the mere ingredients. To begin with, you have to make the mixture, then whip it to make the sauce thicken, etc. Then, you really have to taste it yourself. Even if you have completed these steps, the deeper understanding of the phenomenon will still elude you. All you can do by following the recipe is confirm that the sauce is actually thickening; when it comes to tasting it, what you get is an overall sensation that is more or less pleasant, depending on your taste. But have you grasped anything, really, about mayonnaise and its multiple variations? From a physio-chemical perspective, we are dealing here with extremely precise operations: for example, it is certain specific components of the egg yolk (tensio-active components such as lecithin) that enable very fine droplets of oil (not bigger than a couple of microns) to form into an emulsion when in contact with the water in the vinegar. Chefs know that very different results can be obtained by replacing vinegar with lemon juice. One thing is for sure, you can meditate all you want on the nature of egg yolks, oil or vinegar, until you’ve tried your hand at it you won’t be able to draw any concrete conclusions about what makes this particular cold sauce what it is: a paradox of both creamy and firm, strong and gentle, and so on.

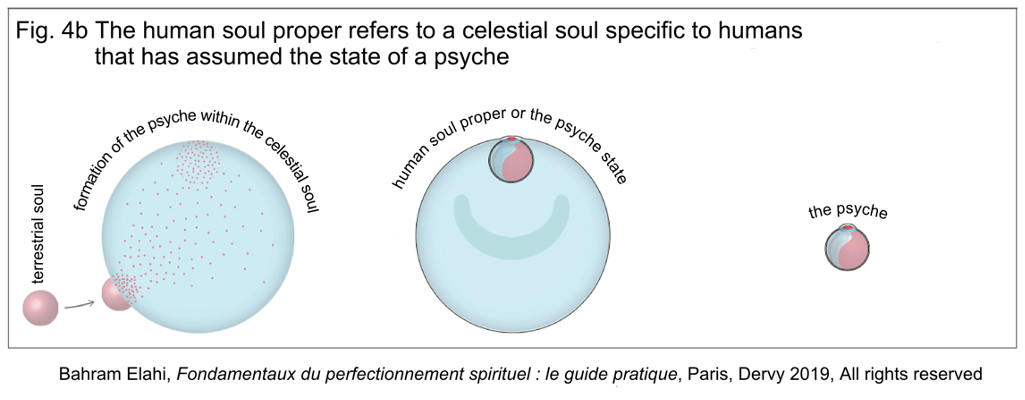

The situation is quite analogous to the result obtained from the combination of the terrestrial soul and the celestial soul. Focusing solely on the components—meaning, on your theoretical knowledge of them—will give you no idea of what kind of chemical emulsion is produced when the celestial soul combines for the first time with the terrestrial soul of a newborn. Now, what does actually take place? Again, we may think we know the answer to this question: the soul dissolves in itself the elements of the animal nature it is associated with and thereby assumes what is called “the state of a psyche” (see Bahram Elahi, Fondamentaux du perfectionnement spirituel : le guide pratique, Paris, Dervy, 2019, figure 4.b). It is at that very moment that “the human soul proper” is formed.

But what exactly is the “state of a psyche”? Again, this is a concrete and therefore precise matter. The state of a psyche refers first and foremost to the emergence in the soul of the sense of self (or of the ego). Not just the self in general, but the sensation of being someone, of identifying as a subject, a subject that can say “I” (as Descartes could say “ego cogito”, “I think” …). The ego in question is an ego that inherits something from the animal, from the instinctive intelligence of the animal. It is a consciousness that is no doubt endowed with reason but also a selfish egoity (see ibid., figure 4b and related commentary). The adjective “selfish” lays it out clearly: it is by virtue of this inborn selfishness or egoism that we human beings have a natural tendency to not only desire what is beneficial to us, but to do so in an exclusive manner, all for ourselves. Therein lies the root of our “imperious self”.

Paradox number one: the imperious self

A paradox immediately ensues. What does actually distinguish humans from animals? You may want to answer that it is the celestial soul of course. And everything that comes with it: reason, moral values, the ability to discriminate between right and wrong, between what is legitimate and illegitimate, etc. This is true, but it is not concrete enough. There is a more subtle though slightly paradoxical answer: what animals lack, and for that matter what angels also lack, is… the imperious self!

Indeed, the imperious self is truly specific to humans. Animals are definitely devoid of any imperious self. They follow their animal nature by exercising their survival instinct to the full. But they are never ever confronted with anything within them that resembles the imperious self. What they lack is a truly selfish egoity. Animals also want everything for themselves, but it is safe to say that wanting them exclusively for themselves is foreign to their psyche. That would require the imperious self, which is the “privilege” of humans. The point is that for the imperious self to emerge in the first place, you need to be endowed with reason, discernment and free will, which together enable you to seek more than your immediate needs and to actively give way to your egoity, thereby transgressing—at times deliberately—that which is moral or divine (see Bahram Elahi, Fondamentaux du perfectionnement spirituel : le guide pratique, op. cit., p. 68). Having an imperious self indeed implies the ability to infringe rights, particularly the rights of others. But this in turn requires that one have at least some basic notion of what a right is, which animals are totally incapable of.

Such is the first paradox: this imperious self that is specific to humans cannot be reduced solely to their terrestrial part; it is an original by-product resulting from the combination of a terrestrial soul and a celestial soul. That is why it is ours to deal with at a most personal, and most individual level. As Ostad Elahi explains, it is by systematically confronting your imperious self, by learning to recognize its thousand faces that you can concretely enter the process of spiritual perfection and ultimately achieve the transformation of your very substance.

Paradox number two: to become human

This immediately leads us to another paradox that is implicit in many sayings: “How easy to become learned, how difficult to become human.” (Words of Truth, op. cit., Saying 379); or “There is a difference between being a human-animal and a human. We are all human-animals, but to become truly human is a difficult task.” (Saying 277). Or in yet another, “When a person becomes truly human, his nature dictates that his actions always be beneficent.” (Saying 4). The paradox lies in the fact that, in reality, at the outset, a human being is not yet human. If humanity is his essence, then he has not yet fulfilled and accomplished his humanity. He must transform the substance of his being to become truly what he is in essence. In fact, as human beings, we are stuck between the human-animal that we already are, and the human that we have yet to become. Becoming human is our project. Could we have deduced this from a mere examination of the notions of the terrestrial and the celestial soul? No. And even less so its concrete implications for our lives.

Portrait of the human-animal

Let us restate these two paradoxes: (1) the imperious self is a distinctive feature of human beings; (2) human beings have not yet become human. Considered together, these paradoxes reveal the issue at stake: to transform the human-animal into a true human, using the battle against the imperious self as a tool. In reality, the task ahead of us involves working on two sides: that of the human-animal and that of the human. On the one hand the objective is to not just be content with being the human-animal we already are, and on the other hand, it is to develop, effectively, the truly human qualities that will make us truly human.

Let us begin by considering the first side. Here the goal of the battle can be formulated negatively: not to limit oneself to being a human-animal. But once again, how should we understand this concretely?

To better understand what is at stake, let us consider the example of an individual we will call Bob. Bob is quite fond of his family, particularly of his partner and his young child that he is raising with her. He is rather sociable and used to be very close to his peers at a younger age. Today, like almost everyone, he divides his time between ensuring his livelihood and enjoying healthy recreations. He engages in regular physical activity and enjoys chilling out. Obviously, he occasionally worries about things, and even has bouts of melancholy when he is suddenly washed over by an undefinable feeling of sadness.

But on the whole, you could say that Bob lives a peaceful life. He turned 33 this year. He weighs 120 pounds and is 4 feet tall. He doesn’t really mind, actually, because in fact, he is not aware of such things: as all members of the pan panicus species, his IQ is around 35. Bob is a bonobo monkey.

This example illustrates the fact that, in many aspects of their existence, human-animals do nothing other than what many animals already do in their own way. With regard to their basic behaviors, such as the search for pleasure, the desire to dominate others, concupiscence or the will to power, humans barely differ from animals. These tendencies can express themselves in either a crude or a sophisticated way, peacefully or harmfully, and of course human beings will add their own personal touch. But in the end, this kind of behavior stems from the same source: the id, which, within our psyche, represents our animal nature. If we are not so different from animals, it is because alongside our human character traits, our soul is also comprised of animal character ingredients.

Ordinary savagery

Let us observe the mandrill in the typical position known by ethologists as the “Do not disturb” gesture. The palm that covers the eyes is not intended to protect from sunlight, it is a signal aimed at others in the group, a sort of “leave me alone” sign indicating the express wish not to be disturbed. Does this ring a bell?

Another typical instinctive behavior in animals—humans included—is territorial marking. In the repertoire of incivilities that ensue, one may mention what is known as the “spread leg” syndrome or “manspreading” among human individuals of the male sex. In public transportation in particular, men have a tendency to spread out and occupy a seat as if they were sprawled on a couch, alone in their living room. Recently, the phenomenon has been deemed disturbing enough to call for awareness campaigns in several cities around the world. As a general rule, commuting on the subway—just like driving a car—are excellent fields of self-study to become aware of one’s own animal tendencies or impulses. Don’t we all, in situations of stress, when jostling through the crowd or competing for a seat, occasionally feel the temptation—at least in the form of a fleeting suggestion—to behave like a gorilla or a mandrill? We should of course consider all the range of behaviors implied by varying degrees of crudeness, sophistication, aggressivity or cunning. Some will spontaneously opt for the blunt approach, by not only blocking the way out but by pushing their way through to be the first one in. Others will experience the same impulses but only inwardly, not acting them out. Why? Perhaps simply because they do not dare to do so and fear being admonished. But in other circumstances, if a fire were to break out on a platform, they would be the first to shove and elbow others to get ahead, going so far as to push children or elderly folks if need be. Outside of these somewhat exceptional emergency situations, one can maneuver the most elaborate strategies to make sure to get a seat on the subway. On the platforms, when there are crowds waiting, some of us are experts at finding the best spot to noncommittally cut the line at the most opportune moment or at stepping in front of the person beside us without even noticing it, to be the first to get on the train. Bonobos or jackdaws wouldn’t do it as skillfully.

There are a good many other examples of aggressive or lustful behavior, of curiosity and greed, of rivalry, vanity, or envy that can be observed among human and non-human animals. There is more to this than superficial similarities. The character traits of animal origin revealed by such behaviors constitute the root of egoity—the egoity that develops in humans in the strictly selfish form of the imperious self. And in more complex and more typically “human” situations than the struggle for territory or mere survival, the question that arises is: are we capable of identifying the bonobo in us? For ultimately, we all have a bonobo lurking within. At times it hides or disguises itself, but it is always there. A self-help book designed to address this issue would go something like: Finding One’s Inner Bonobo…

It is true that habits of civility and politeness acquired via our upbringing or under the pressure of social conventions generally keep us from unleashing our inner animal nature. Roughly speaking, we keep ourselves checked most of the time. The problem is that there are sophisticated and apparently very “human” ways of behaving like animals. Think of the slightly sneaky way we dexterously maneuver to bring the topic of a conversation towards a person we are jealous of, in such a way that our interlocutor—certainly not us—begins to speak ill of the person. Consider the slightly dubious eagerness with which we sometimes reprimand someone, or simply let them know they did something wrong. We teach them a lesson under the pretext that we have a good reason and that it is indeed our right to do so, while in reality we are clearly blowing off steam and satisfying a twisted desire for revenge or humiliation. Crushing people, possibly to self-aggrandize, can be done using words or simply adopting a tone. No need to get physical.

Maliciousness, meanness, stinginess, boastfulness, jealousy, vanity, many more examples could be given by systematically skimming through the list of character weak points. It would take an entire menagerie to depict the subtler undertones. The psychological motives of such attitudes are obviously more complex than those that can lead us to jostle other people on the subway; but the animal metaphors are definitely relevant when used in expressions such as “sly as a fox” or “mean as a snake”. All our moral failings, and all our character weak points include a tinge of animality. When evoking certain weaknesses, we often hear “It’s only human…” and it wouldn’t take much to find them touching. But the truth is that these traits are 100% of animal origin, despite being refined and processed to fit the human kind.

Bob

[to be continued…]

This work is offered under a Creative

Commons licence

This work is offered under a Creative

Commons licence

News

News Podcast

Podcast

Thank you for this thought provoking article and for elucidating so many nuanced points!

Looking forward to part 2!

Thought provoking article.

“…the goal of the battle can be formulated negatively: not to limit oneself to being a human-animal…”

“…the question that arises is: are we capable of identifying the bonobo in us? For ultimately, we all have a bonobo lurking within. At times it hides or disguises itself, but it is always there…”

Reflecting on the above sentences, I was thinking that in the court of law the basic assumption is; “everyone is innocent until proven guilty”. It appears that my psyche, by default, operates under the same basic assumption concerning my imperious self (that nothing comes from my imperious self unless proven otherwise). This base assumption is wrong and so harmful to my soul. It would be beneficial to consistently scan my psyche to override this tendency by adapting the opposite assumption. Hence, my inner dialogue should be something like “everything you do (acts, feelings, decisions, wants, etc) come from your imperious self unless proven otherwise.” So the burden is on my soul to prove that a certain act (feeling, decision, want etc) is not from my imprisons self, and hence, is from my inner guide.

Even though in the latter (overriding my psyche’s basic assumption) the imprisons self is still skillful enough to prove its innocence in many cases, but at least my soul will have some homework to do, and there is a chance to win, while simultaneously throughout this struggle my sound reason will gradually develop, whether it wins or loses. However, in the former (not overriding my psyche’s basic assumption), my imperious self has nothing to be worried about at all, hence, it will achieve its goal with maximum efficiency, at no cost of its own, but to the deferment of my soul.

The article had me until the mayo analogy. After that I was lost. Why do I need to know the ingredients of mayo at molecular level? All I need is to know in which food/salad I should use it and how much. In the same manner, evolutionary, we are designed not to have high-resolution on anything to be able to function in the society. Why is it different for spirituality?

With thanks for such a great subject which made me think. Now, is there any way to somehow recognize where we are in the range between truly human and bonobo human?

Thanks for this amazing article. I’m practicing to identify the bonobo in me. I’ve read a bioscience animal brain research article where they said the sense of right and wrong is not unique to humans. Chimpanzees also discriminate in terms of deciding what behavior is inappropriate, especially when it affects young and baby chimpanzees. In a study carried out at the University of Zurich and which was published in the journal Human Nature, it became evident that if a chimps scenes of a baby being harmed or killed by another member of its own species, it reacts with indignation and anger, something which does not happen in cases of violence among adult monkeys. The study indicates that these primates have a sense of morality that is similar to that of human animal.

Dear Naghme,

I think the Bob story precisely implies the opposite.

If you see the diagrams of Bahram Elahi, animals are pure ego, totally act with their instinct and don’t have a sense of right or wrong in the same way humans do (1+1=3 is “wrong” – meaning false –, and animals have a similar instinct that we can call “discerning what’s wrong”, but this is different from understanding that stealing is “wrong” – meaning contrary the laws set by the One). Most current scientists don’t believe in the fundamental difference between humans and (other) animals and it creates a series of false assumptions.

The humanization of animals is often used to lower the status of humans and to totally animalize them by saying, in particular, that true altruism does not exist. This article is based on the idea that the soul exists (with a celestial part), and coming from it altruism (in humans), but indeed, if we don’t pay attention, it’s like other animals.

This has a practical outcome. To me, the most striking point of the Bob story is precisely to point out that any behavior we share with animals is… of animal nature, so in itself, it does not help us become actually human. It does not mean it’s bad to have leisure, take care of one’s family, etc., but it means it is not good enough, in itself, if one’s goal is perfection. We are talking about altruism, but also intention in animal acts. For example, if you have children, why do you do all of these efforts? Raising children can be very rewarding socially or for the ego (we live through the children, which leads for example some parents to model the life of the child according to what they would have liked their life to be; pride, etc.). If you correct your intentions and make everything spiritual, many acts will be externally the same, but there will be crossroads and choices to make, that will test what your intentions were all along (you might even not see these crossroads if your intentions are not spiritual).

Most of the article focuses on the question of “small” “everyday” evil acts though, which is linked but different, I think.

To me, the assessment of so many things as animal is quite unpleasant (for a series of reasons I’m not sure it would be useful to analyze here; basically it removes to a very large extent the “taste” of this world in itself; I discuss it a bit there https://www.e-ostadelahi.com/eoe-en/unfaithfulness-of-the-world/#comment-843901 and there are in particular references to World of Truth you can look at). But if what we care about is the Truth… And it is because we are not at a level to actually feel and “taste” the Truth, which is the most pleasant thing of all in reality. We cannot do better than the perfect world God created, any other feeling stems from our illusions and weaknesses. But that’s ok, we just have to live with it I suppose, I don’t know.

Thank you for sharing this amazing perspective. I have seen it in myself. I used to act very similarly during my younger days, but based on Ostad Elahi’s teachings, I have tried to correct myself and not act like this any longer. But still from time to time, I think about it. I am trying to get to a point where I am not even thinking about it, which is much harder.

It would be great in future articles to discuss how to control and stop thinking about such acts.

Thank you for this wonderful article!

Among many practical points, most important in my case is to catch my own hand and identify the sophisticated and apparently very “human” ways of behaving like a human animal.

I know I need to lay my groundwork in this area, I see it in myself:

“Consider the slightly dubious eagerness with which we sometimes reprimand someone, or simply let them know they did something wrong. We teach them a lesson under the pretext that we have a good reason and that it is indeed our right to do so, while in reality we are clearly blowing off steam and satisfying a twisted desire for revenge or humiliation. Crushing people, possibly to self-aggrandize, can be done using words or simply adopting a tone. No need to get physical”

To be a sophisticated human animal is still far from being “human”!

“It would take an entire menagerie to depict the subtler undertones.”

“All our moral failings, and all our character weak points include a tinge of animality. When evoking certain weaknesses, we often hear “It’s only human…” and it wouldn’t take much to find them touching. But the truth is that these traits are 100% of animal origin, despite being refined and processed to fit the humankind.”

The above points hit home in a deep way and at the same time, it’s very heartwarming to know that our guiding light is still shining as bright as ever, only if we are willing to seek and walk the path.

Thank you, I am grateful as always.

Dear Yan, thanks for your comment, but I find it difficult to find the guilty party in court. When I see my everyday actions, except for some ordinary actions (cannot be certain), all of them somehow have a bonobo smell to them. So that it’s very undesirable. Although I am working hard to change the situation in favor of my soul.

Thank you for this article. It is amazing.

Thank you so much for this meaningful article.

It really is an eye opener, to be taken very seriously.